Connecting Health Communities

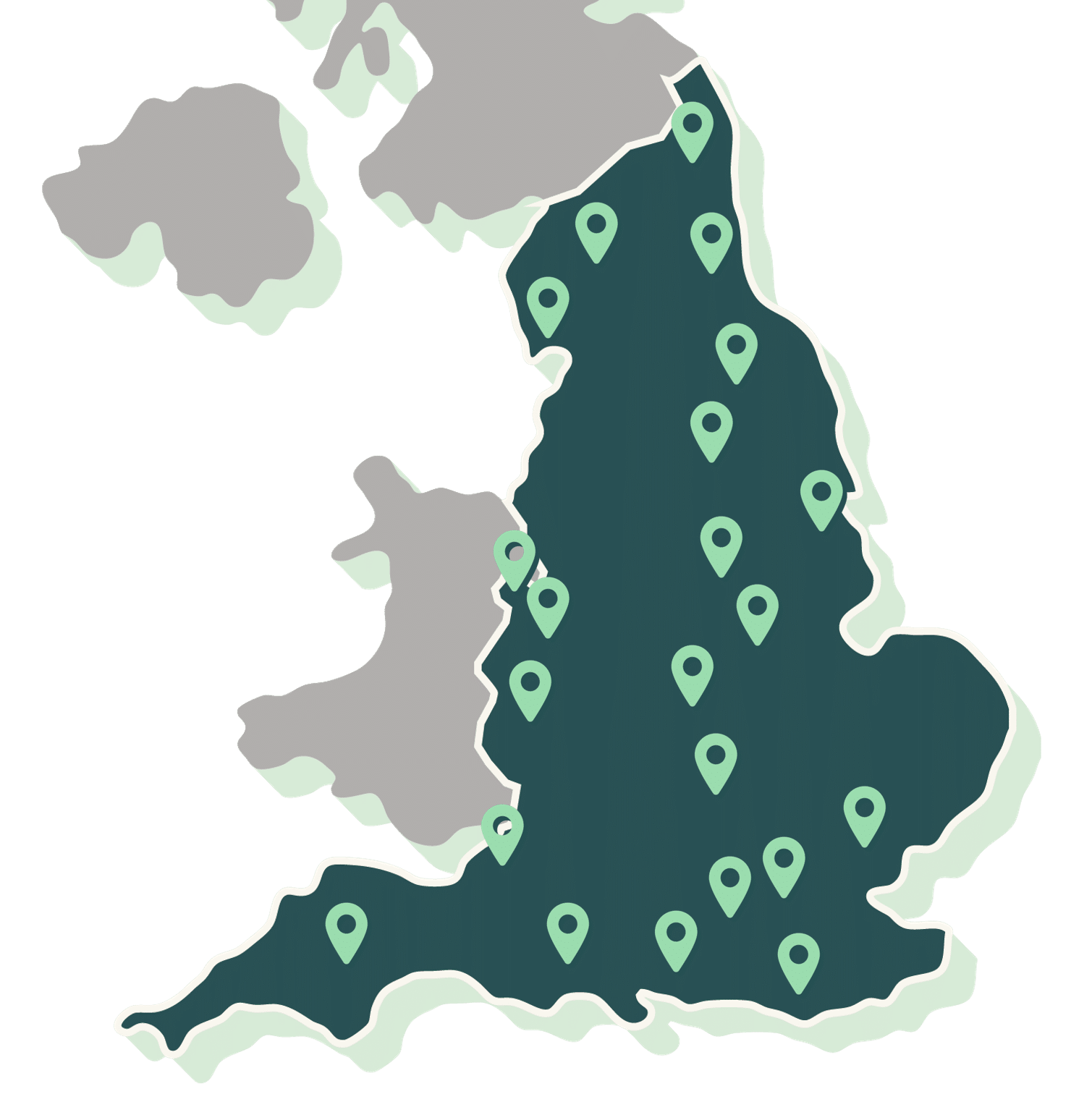

We support cross-sector partnerships to tackle health inequalities.

Introduction

We’ve been facilitating cross-sector partnerships to develop practical responses to local issues for over 18 years. We have enabled groups to reach their most isolated and vulnerable community members, ensuring that services meet local needs.

This page shares our learning about how voluntary organisations and local systems can work together to engage with complexity and achieve change: from co-production in Primary Care Networks (PCNs); to sharing learning across the Integrated Care System (ICS).

How we support cross-sector partnerships

Our offer and aims

What is Connecting Health Communities?

Connecting Health Communities involves activities for a ‘steering group’ and a wider ‘partnership group’ as described below:

- Steering group: Key stakeholders from across the local area, representing the cross-sector group, who (with the support of IVAR facilitators) drive and support the work outside the facilitated sessions. Usually a group of eight or more people, it is important to have the involvement of community leaders and NHS representatives.

- Full partnership/Co-designing days: Involving all interested parties within the local area. The steering group seeks representation from across sectors, as well as community voices to shape and take forward agreed activity. These sessions usually involve around 30-60 people. Workshops are ideally in person; however, they can take place online (e.g. Zoom/Microsoft Teams).

- The Champions Network: A group of cross-sector leaders who want to develop their skills for collaborative and partnership working through peer learning. The overall aim of the Champions Network is to enhance confidence and competence to become system leaders and agents of change. Together, members of the network will share ideas and ways of working, and devise strategies to maintain and build on the practice of collaborative working to support action and sustain change in their areas.

- Local coordinating organisation (LCO): An organisation (or organisations) based locally that support the involvement of communities experiencing health inequalities. The LCO is responsible for cascading information following each co-design/partnership session; and coordinating with other communications leads in the local area to disseminate national learning through their networks. There is a small budget to support these organisations working predominantly at a local level, if money is a barrier to their involvement. The LCO is identified with the facilitator and steering group when the local area conversations begin.

- Community involvement budget: For partnership working to be genuinely cross-sector, we understand that voluntary organisations and people with lived experience need to be able to participate and contribute fully, and be at the forefront of leading action for change. There is a small budget available to help cover attendance costs as well as the time of people who take on a more action-focused role in the area.

Our approach

The model that we use for Connecting Health Communities is built around a deep commitment to listening and collaboration. We aim to address health inequalities by bringing together people with lived experience, charities, the NHS and local authorities to co-design solutions. We involve around 100 people in each area, and we prioritise:

- Building relationships for joint action

We create space for the building blocks of partnership working by:

- Connecting people

- Helping them listen to and understand each other

- Identifying a shared starting point for action; and setting realistic and achievable goals

- Acting as Advocates for the community

Our entry point is to champion, promote and enable the voluntary sector to be a valued and influential partner in health and care design and delivery. We privilege the perspectives and voices of people who are furthest from power in our work.

- Flexibility

We have a core offer that we adapt to work for each area we partner with. We notice when things aren’t working and change our approach to meet the needs and circumstances of local partners.

- Style of facilitation

We take an inclusive, fun and human approach – starting with who is in the room, acknowledging emotions and recognising past challenges. We then use creative methods to facilitate difficult, cross-sector conversations which lead to action. This helps to build capacity locally and is itself an act of influencing the local system, by modelling a collaborative approach to problem-solving.

- Taking responsibility to maintain momentum

We play a convening role, holding the process and bigger picture for the partnership as collaborative working gets underway:

- We ensure that next steps are jointly agreed, and that follow-up actions are picked up.

- We tell the story of the work as it evolves, keeping people energised and motivated.

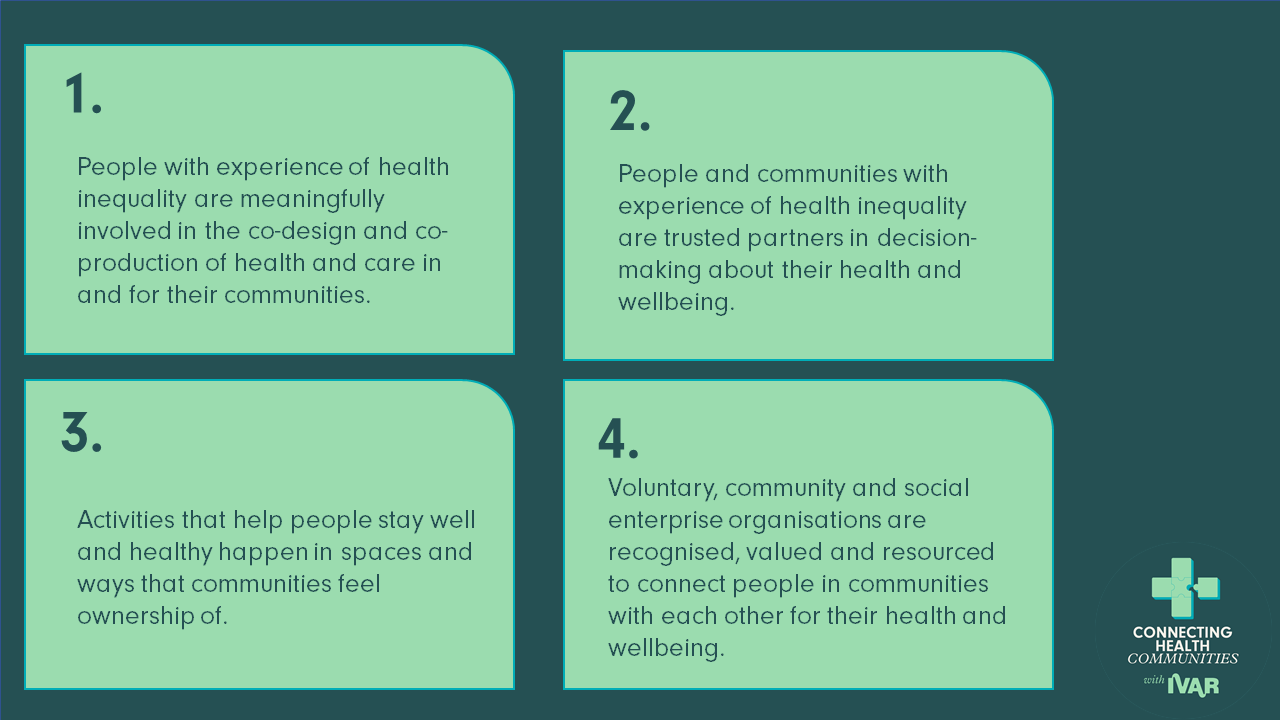

High-level aims

Meet the areas we’re currently working with

We’re currently working with four areas: Barnet & Enfield, Birmingham, East, Dudley, Leicester & Leicestershire and Somerset. Each has a unique health inequality focus.

- Barnet & Enfield aim to enhance access for disabled patients through collaboration among disabled people’s organisations, the voluntary sector, the NHS, and local public health.

- Birmingham aims to strengthen partnerships to address health disparities affecting sex workers, ensuring their voices drive improved healthcare access.

- Leicester & Leicestershire aim to develop a comprehensive homeless health package, bringing together diverse voices and key organisations to explore strategies for effective healthcare delivery.

- Somerset aims to develop a scalable approach to improve discharge experiences for people with dementia, informed by patient, family, caregiver, and health system perspectives.

Challenge, Action, Outcome: Find out more about the aims for each of these areas here.

1. Getting started

We support local areas to build partnerships where no meaningful cross-sector relationships exist.

For example:

A local NHS system was created in Bristol, North Somerset and South Gloucestershire – a large new geography. We brought cross-sector partners together with the broad aim of better understanding the needs of their population. This was a particular challenge due to historic and increasing competition for contracts amongst community organisations. Through a series of workshops, we re-set relationships and established a Social Prescribing Expert Group. This enabled more effective communication between the voluntary sector and the NHS, culminating in the group working together to promote and deliver a consistent social prescribing offer across the new region.

Resources:

Delayed Transfers of Care and the Voluntary and Community Sector in Greater Nottingham: Findings and Recommendations

People, places and health agencies: Lessons from Big Local residents

2. Getting to the next level

We enable areas with an existing cross-sector partnership to translate good intentions into actionable plans.

For example:

In Oldham, working with a recently established group of statutory colleagues and voluntary sector organisations, we ran a workshop to demonstrate the impact of partnership working and develop action plans for the future. The workshop focused on developing a collective evidence base rooted in local practices, to better demonstrate the impact of partnership working. It resulted in agreement between over 30 organisations, across sectors, on a common approach to co-producing services and to commissioning, which will support funding decisions about local health and care services.

Resources:

Copeland Community Stroke Prevention project: This report is based on the work undertaken through Building Health Partnerships (BHP) in North Cumbria and the Copeland Community stroke prevention project. The project wanted to help people identify potential risk factors and raise awareness of lifestyle choices that can improve their health.

What would enable sustained transformation in cross-sector working in the long term?

3. Making it stick

We support existing partnerships to make changes at the system level.

For example:

In Worcestershire, the voluntary sector felt like an equal partner to the NHS during the immediate Covid-19 response. We facilitated a cross-sector workshop to understand what was different, and how to make that way of working stick. A clear set of actions was developed – from joint planning to sharing office space – which was included in the refresh of the area’s local Long Term Plan.

Resources:

How to build an effective partnership: In Lancashire and South Cumbria, statutory and voluntary sector professionals have been working together to design, test and deliver improved health outcomes for local people.

Trust, power and collaboration: Human Learning Systems approaches in voluntary and community organisations. This report shares practical tips for taking a ‘human learning systems’ approach to commissioning and funding relationships.

4. Getting unstuck

We support areas who are already involved in collaborative working to address challenges on their partnership journey.

For example:

In North Cumbria, we rebuilt relationships between the NHS and communities following the controversial decision to combine two stroke units into one hyper acute stroke unit. People were understandably very concerned: 85% of strokes are preventable, yet in one area in West Cumbria, people were 104% more likely to have a stroke than the national average. We enabled cross-sector partners to identify local events where stroke prevention messages could be shared. This led to over 200 people being tested for stroke risk at community events, with over 20% being referred to their pharmacy or GP.

Resources:

Talking points for cross-sector partnerships: Questions to use when exploring new and existing ways of working in partnership at Integrated Care Partnership level, with the aim of finding out more about what things look like now, what can be learned and what needs to be changed/developed.

5 things that help system leaders ‘have difficult conversations’: Blog highlighting the lessons from leadership workshops with cross-sector leaders.

Resources and learning about…

Useful resources for health partnership working

Below, we’ve collated a list of the most helpful resources for building cross-sector relationships that improve community-based healthcare.

Collaborative working in complexity: Practical learning points and reflections for people at the beginning of working across organisational and sectoral boundaries to tackle complex challenges.

Moving to action and growing pilot projects: Practical tips provided by health and care leaders on getting started and growing pilot projects.

Measuring impact: Practical tips provided by health and care leaders on measuring the impact of projects.

Trust, power and collaboration: Suggestions for taking a ‘Human Learning Systems’ approach to commissioning and funding relationships.

Barriers are coming down: Community-based healthcare during Covid-19 and the challenges and opportunities facing cross-sector leaders.

What good looks like: An example of cross-sector working in Pennine.

How we set up a social prescribing service during lockdown: Two social prescribing link workers in Lytham St Anne’s Primary Care Network reflect on their role.

A Community Action Network in West End, Morecambe Bay: Set up to improve local lives through sharing resources, seeking investment, supporting each other, and involving local people in the conversations and decisions that affect them.

How to build an effective partnership: Nine puzzle pieces for creating connections that enable meaningful collaboration, based on Lancashire and South Cumbria’s aproach.

A toolkit for conducting community research: Produced to support community researchers looking at delayed transfers of care in Nottingham and Nottinghamshire.

12 steps to embedding social value priorities: A tried and tested framework for commissioning authorities, VCSEs and service users to agree and implement social value priorities in health and care commissioning.

Know Your Numbers: How Local Action is Preventing Strokes in Cumbria

“What could we do to prevent people having strokes in the first place rather than waiting for them to get ill?”

In 2019, the community of Copeland in West Cumbria faced two urgent challenges: stroke rates that were up to 104% higher than the national average, and difficult changes to local stroke services.

Find out about the Copeland Stroke Prevention Project below…

Case studies

By: Amanda Sayer, Business and Managing Partner, The Lighthouse Medical Practice, Eastbourne; Kay Muir, Senior Partnerships Manager, Health, Wellbeing and Inequalities, NHS Sussex-East; and Mebrak Ghebreweldi, Director, Diversity Resource International

Improving access to cancer screening in Eastbourne, East Sussex

The uptake of cancer screening is low in East Sussex among culturally and ethnically diverse communities. In 2022, we – a cross-sector group of health and VCSE partners – came together to understand why that is and to find a solution with an overall focus to ensure health equity in East Sussex.

We started by listening to people in the community to build an in-depth understanding of why they were not accessing cancer screening – aware that each person’s experience is different. Across the board, we heard wide-ranging barriers that can make it challenging for people from culturally and ethnically diverse communities to access healthcare, for example, language and communication barriers and a lack of cultural sensitivity in some healthcare providers’ approaches.

From a strategic commissioning approach [for the East Sussex CCG], this [Connecting Health Communities] felt like a great opportunity to get direct insights from our communities, combined with facilitating cross-sector working, so we could really drill down into what was happening locally and share expertise across the partnership to address these issues and improve access to cancer screening among culturally and ethnically diverse communities in East Sussex.

Who was involved?

Our group comprised a diverse range of professionals spanning the Integrated Care Board (ICB), social care, healthcare providers (e.g. GP surgeries), Primary Care Networks (PCNs) and the VCSE sector, alongside public health colleagues and local community leaders. One key player was a local non-profit social enterprise, Diversity Resource International (DRI), who recruited six community leaders from five countries to represent the views and experiences of culturally and ethnically diverse communities.

Our membership grew through the lifetime of the project, with members often recommending colleagues working in related areas to become involved:

It was brilliant to connect with people from different sectors – but also from different NHS organisations. People always see the NHS as one organisation, but it’s made up of a lot of smaller, often disconnected, organisations and roles. We came to understand people’s perspectives on health, but also how to work together.

What did we do?

When we expressed our interest in Connecting Health Communities, our focus was on using this work ‘to sustain partnership working and to improve the delivery of health outcomes for groups experiencing the worst health inequalities’:

We started with an ambition to improve cultural competency and better health outcomes with an overall focus on health equity, but this topic felt very broad. We had to hone our focus down to something tangible. We proposed cancer screening, as my Clinical Director [at the ALPS Group PCN] had identified lower uptake among some communities, and it was an area where we could measure progress.

We decided to focus on the seaside town of Eastbourne, going where there was energy to try something different, building on the work through the Primary Care Network (PCN). Amanda Sayer, Business and Managing Partner of the local Lighthouse Medical Practice, volunteered on behalf of the ALPS Group PCN, which covers 50,000 residents around the town. The six community leaders recruited by DRI participated in the discussions and we began to understand better the problems people face in accessing healthcare and why they might not attend cancer screening.

Barriers leading to low take-up of cancer screening among culturally and ethnically diverse communities

- Language/communication barriers: Although interpreting and translation services were in place, they were often not available/accessible at the point of need.

- Lack of clarity around the screening letters: The standard template letters inviting individuals to screening were difficult to relate to or understand. Individuals were unclear about what screening is available and to whom.

- Practical challenges accessing screening: For example, digital exclusion, transport challenges, and difficulties for residents with no permanent residency, as they are less likely to be on a screening list and/or receive invitations to screening.

- Lack of clarity about clinical procedures: For example, fears that colon cancer screening will entail an embarrassing, invasive intervention when, in fact, it is self-managed at home.

- Challenges in understanding how to navigate UK healthcare: ‘I don’t know where to start, who to speak to, or what help is available’ (Community Leader).

- Limited resourcing for targeted/tailored approach to screening: Staff shortages mean it is not always possible for individuals to request a male or female doctor/nurse.

- Lack of cultural sensitivity in some healthcare providers’ approaches can lead to different cultural or linguistic ways of patients’ articulation of medical issues being dismissed by some healthcare professionals.

- Fear of sharing private symptoms with family members or professionals interpreting on the person’s behalf, as well as the impact this might have on family members, such as children interpreting cancer diagnoses for their parents.

In addition, DRI and two of the community leaders attended some local women’s cultural groups to speak to them about cancer screening:

Enabling access for women is often the first step in engaging the rest of their family members.

Through the course of our workshops, we decided to focus on four activities, each led by its own subgroup:

- Developing bespoke cultural competency training for GP surgery staff across the Primary Care Network (PCN)

- Making recommendations to NHS England screening leads about how to make screening letters clearer and more accessible

- Reviewing communication and support services, such as interpreters and translation, and sharing learning

- Engaging communities in health inequalities discussions

What’s happened through this work?

The East Sussex Connecting Health Communities work has led to the following actions in relation to the take-up of cancer screening for culturally and ethnically diverse communities in Eastbourne, as well as having wider implications for cross-sector working in East Sussex:

1. Bespoke cultural competency training for GP surgery staff

Based on the insights of the community leaders set up by DRI, the partnership has developed a package of bespoke cultural competency training for frontline staff, such as receptionists and administrators.

The training was delivered to four GP practices in July 2023 and was attended by over 40 primary care receptionists.

A tried and tested training programme has been produced (with resources and identified leads) and could be rolled out across the whole of East Sussex, and potentially Sussex PCN GP practices.

The partnership is keen to examine before-and-after screening uptake figures, although it will be some time before there is clear evidence of impact. In the meantime, teams will gather qualitative insights into what is changing.

2. Making screening letters clearer and more accessible

The NHS Sussex Cancer Programme Lead and Public Health Lead have been working with local communities to continue to improve and understand how best to reach and work with local culturally and ethnically diverse communities to access cancer screening.

3. Contributing to the review of interpreting and translation services

Having developed a much more nuanced understanding of the barriers to accessing translation and communication support services through the Connecting Health Communities discussions, the partnership was able to provide feedback on other consultations into these activities locally. The NHS Sussex Commissioning Lead for Translation and Interpretation Services has been involved in discussions and fed back to the group about newly commissioned interpreting and translation services.

4. Community engagement

A core discussion within the communications sub-group set up through Connecting Health Communities has been looking at tackling low community awareness of cancer screening programmes, which limits people’s ability to make informed decisions about accessing them.

Separately, Mebrak has set up a monthly walking group for the women who participated in the project, combining a healthy activity with discussions about how to continue improving access to healthcare. The group is currently seeking funding to transport women to rural locations on the South Downs.

5. Better partnership working

The partnerships forged through the East Sussex Connecting Health Communities work have helped to establish better partnership working in general between some of the organisations and individuals involved:

Recently, I needed to plan some health checks for asylum seekers living in hotels. I was considering how to approach it, then I thought, “Oh – Mebrak and her organisation know about that.” I realised that I now know people who I can link up with to share advice and learning. That’s been a huge, huge thing for me.

By: Caroline O’Neill, Head of Community Support and Partnerships, Community First Yorkshire; and Julie Lawrence, Former Project Manager, South Hambleton and Ryedale Primary Care Network

Improving rural access to healthcare in North Yorkshire

A partnership of voluntary, community and health organisations set out to improve access to healthcare and wellbeing services for three rural communities in North Yorkshire by exploring specific solutions tailored to the needs of local communities.

North Yorkshire is predominantly (85%) a rural area and is the largest rural county in England. For residents, this means access challenges that are particularly felt in later life – such as reaching GP and hospital appointments. Public transport is sparse, taxis are expensive, and local community transport mainly consists of volunteer drivers using their own cars and with precarious funding, making it difficult for people to travel to hospital appointments and access the healthcare they need:

It’s not just the case of a missed appointment or two: for older people, missing appointments can have life-altering consequences, like acute health problems or the need for social care. This goes beyond individuals, and places strain on the health system. When patients miss appointments, it can present operational challenges, like lower uptake of screenings and appointment backlogs.

The North Yorkshire Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) reported 29,508 ‘no-show’ appointments in 2019 at an estimated cost of £885,240 in lost consultation time, which is significantly higher than in other areas. Similarly, cancelled appointments at short notice create a significant cost for community transport providers: ‘Distance equals delay in accessing health and care services’.

Rural residents face higher costs and greater difficulty accessing specialist and emergency services, and the distances cause delays in access to healthcare – increasing the health inequalities faced by rural communities.[2] James Cook Hospital lies outside the county, in Middlesbrough, and is the largest in the area with a 24-hour A&E department and specialist services, which communities need to access regularly: ‘For many residents and patients, the journey time can be as long as two days for a round trip, when the national average is 60 minutes’.

We were very aware of the scale and the range of complexities and challenges from both sides, and we felt compelled to bring partners together across the health and voluntary sectors to strengthen the ties between us, and work together to improve access to healthcare and wellbeing services for residents.

Who was involved?

We are a cross-sector group with Community First Yorkshire, Hambleton Community Action (HCA), Nidderdale Plus Community Hub, Next Steps, Pickering Medical Practice, North Yorkshire Council, Healthwatch North Yorkshire, Humber and North Yorkshire Health and Care Partnership, and the MoorsBus, working together to develop workable models to improve access to healthcare appointments and wellbeing services.

In February 2022, we reached out and brought together cross-sector stakeholders, including voluntary and community groups, community transport, ambulance services, service users, GP practices, Primary Care Networks (PCNs), hospitals, leads in the Integrated Care Partnership (ICP) and Board (which were all still being formed at the time) and service users to understand what is essential for patients and people in the community when they think about transport for health and care, including safety, cost, accessibility, comfort, navigation and communication about available transport options.

We selected three neighbourhoods with known access difficulties that were also home to organisations keen to be involved and interested in looking at a range of solutions: Hambleton and Richmondshire, Nidderdale, and North Ryedale. The emphasis of this work is on people with existing inequalities and challenges accessing health and social care interventions or activities, lack of advocates in the community and/or lack of a support system, all of which were affecting their access to healthcare.

What did we do?

Our workshops brought together people from the community and staff across the health and voluntary sectors to scope out how to access healthcare. We aimed to design models that would improve the situation. To be effective, each needed to be designed in a way that would work at a practical level.

The first workshop in February 2022 was a virtual meeting with more than 60 attendees. Later workshops took place in familiar local venues, such as village halls, to ensure residents from the local areas could attend. These workshops usually had about 20 attendees, including three to four service users.

Our workshops were structured but informal. Throughout our conversations, one regular activity, ‘Wouldn’t it be brilliant if …’, enabled people to imagine solutions without parameters. For example: ‘Wouldn’t it be brilliant … if rurality was recognised as a health inequality and every policy or plan had to be rural-proofed for our communities’.

Later activities were more action-oriented, exploring barriers to change – such as a lack of clarity about who to phone for community transport. People were very realistic about what was possible, and not all of the ideas required money: it was more about changes to how we all work together, talk to one another and support people.

Examples of barriers to accessing healthcare

Not everyone meets the threshold for the ambulance service to pick them up. Those who do might be charged £40–80 and some use ambulances several times a week. People were unsure how to arrange other forms of community transport. Where people knew how to access transport, appointments provoked high anxiety levels due to the complexity of making these arrangements.

In Hambleton and Richmondshire, we focused on transport integration through expanding the existing Hambleton & Richmondshire Rural Transport & Access Partnership[3] (RTAP). We revisited volunteer involvement; communication and coordination for transport users by working with GP surgeries and others, for example trying to group non-urgent appointments and bringing integrated services to communities.

In Nidderdale, we integrated community patient management, by developing a closer working relationship with Harrogate Hospital and the Volunteer Manager at the hospital, for better transfers of patient care from community transport drivers and for appointment grouping, exploring how community transport can benefit services and the people using them.

In North Ryedale, we took services into communities, exploring volunteer-led digital access and digital consultations at local hubs, by expanding the conversations and wider engagement in the existing Community One Stop Hub.

Overall, ‘the culture was one of openness and making sure everyone had an equal voice. It was very professional but still informal’. We didn’t start with preconceived ideas – it was very much driven by local conversations, with each community focusing on areas they were interested in and building on their existing connections and work. After all, it was local people and local groups who would be making things happen. We’ve seen this energy and ambition create a difference:

What gave me most pleasure is the way everyone wanted to work together. Detailed practical actions and longer-term possibilities were being shared and shaped by everyone who has a part to play in the health system. We’ve seen lots of energy and ambition to create a difference.

What’s happened since our workshops?

In North Ryedale, the Community One Stop Hub – a VCSE-led centre by Next Steps and Carers Plus – where local groups come together to discuss issues, has extended its services to low-level health checks. During and since the project, more PCNs have become involved, along with GP practices planning quarterly outreach clinics, and taking blood tests and blood-pressure readings at the village hall:

For us at the PCN [South Hambleton and Ryedale], we’re seeing a definite shift in the way the NHS is working. The collaboration we saw in this project – alongside new roles such as social prescribers and wellbeing coaches – is making primary care more connected with our communities.

For us at Next Steps, our key learning has been around how to target this to work, i.e., bringing in the right people and managing the logistics of doing this work well. It is also about how two VCSE organisations are working well together, playing to their strengths and having funding in place to support the work. It really shows the importance of communication and the results from the intent of working well together.

Getting started: Building relationships and effective engagement with PCNs

- Know their agenda: PCN contracts highlight their role in reviewing their population health management data for health inequalities. PCNs have plans in place to co-design and implement interventions to tackle those inequalities. Any work that aligns with that task is their agenda and they’ve been keen to work with organisations/models trying to improve health for their population groups.

- Understand the budget available: Given the current situation with budgets, the key is to ‘work cleverer and smarter and better together, rather than work with/ wait for new resources for new services’. It is important to establish better ways of working together.

- PCNs are keen for collaboration: Knowing their role in primary care and needing to work with various population groups through Healthwatch and other VCSE organisations, PCNs are keen to work in partnership and to support existing services ‘rather than set-up new shiny services’.

- Have a clear action plan: Having ready plans for funding from the ICB can help, i.e. have data/tested models and have action plans that tackle inequalities ready for discussion.

Some Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

- How can we know who the key players are in our area? Speak to someone who manages PCNs and ask who in the PCNs are the right people to speak to. It might not be the Practice Manager or Clinical Director, but someone who has a more strategic role.

- How can we develop ways to share knowledge between PCNs and us? Develop relationships with key contacts who have strategic roles, so that knowledge, feedback and insight between VCSEs and PCNs can be shared.

- What do we do when the person we have built a connection and relationship with leaves the organisation or their role? ‘Rebuild the connection with the new person!’ – if there is a handover period, meet the two people together (the one who is leaving and the one taking over their role).

In Nidderdale, we have developed better links with the hospital to make transport run more smoothly. For example, ensuring that someone is available to take the person to their appointment and, if they do, that there is somewhere to park. Nidderdale Plus is delivering a pilot around the provision of adult social care with a community element, focusing on stronger community links to support and recruit local carers. It explores how to embed a transport element within this to enable people to access the care and support they need easily. Alongside this, we have a Digital Champions Project with regular outreach sessions, called Coffee, Click and Connect, based in village halls where people turn up and get help to go online, to improve their digital skills to use devices they have been given, and to build their confidence to access online appointments from their homes.

In Hambleton and Richmondshire, we are looking at extending the rural community transport model, alongside working with PCNs to explore the clustering of appointments led by HCA. HCA has also started exploring ways to bring services to communities via monthly hubs (with six place leads and six thematic providers) to improve people’s access to health and wellbeing services. HCA is also doing a research piece engaging with social prescribers, mental health practitioners and others to explore their transport priorities, and also try and understand PCNs’ transport priorities.

What did we achieve through working in partnership?

Overall, the work in North Yorkshire has raised the profile and importance of working together to have alternative ways of easing access to health appointments, including the need for closer engagement with transport providers, particularly community transport.

It has showcased the breadth of VCSE sector activity (and its role in health and wellbeing in communities) to various partners on the steering group and in workshop sessions.

Three models developed: As each of the three areas chose its approach, different models are now emerging. These add value because they produce three learning areas that can be tested and applied elsewhere, with potential for growth.

Better access to health and care services for patients: We have been able to inform the right patients about the right services in larger numbers, rather than one-to-one, and ensure that services are designed to suit patient needs. One unintended benefit has been reduced isolation when people travel to appointments or services together:

A lot of people using community transport are fairly isolated, so an unintended consequence is that it is focused on bringing people together and supporting one and other, especially when they are in quite a vulnerable situation.

Power of word of mouth: Not just between partners but also between people where the work is happening in the areas that have been supported. For example, other areas are already adapting the approaches for their own needs. At one event held in Hambleton and Richmondshire, local authority representatives from nearby Craven District attended and have since set up a similar group there.

Motivated colleagues continue to make changes and work in collaboration with partners: The project has forged a more joined-up partnership approach, building new relationships between PCNs and local organisations and a better understanding of each other’s priorities. Over 100 colleagues, patients, and system leads have been involved in this work and it has influenced peers and the whole system to work together:

It is not easy doing this alone, and this programme has helped recognise the potential and encouraged people to keep trying and not give up, which is really powerful. There was a real enthusiasm from all involved to move towards the “wouldn’t it be brilliant if” ideas.

Next steps: The NHS is considering providing longer-term funding for community transport, recognising that this may help ease hospital pressures. The steering group will continue to meet. Now that new connections have been made, the plan is to continue to work together. In a period of system evolution and change, the connected approach is fundamental and provides a basis for collective responses to the peaks in demand for NHS services. It means the core people central to this initiative will continue collaborating, irrespective of who they work for.

By: GP Dr Tom Holdsworth, Clinical Director for Townships Primary Care Network and Laura Davies, Nurse Practitioner, Hackenthorpe Medical Centre

Reducing smoking in Hackenthorpe, Sheffield

Noticing higher levels of smoking and deprivation in one of its areas, Hackenthorpe, Townships Primary Care Network (PCN), near Sheffield, decided to develop a partnership approach to better understand and tackle this area of health inequality.

The decision to focus on Hackenthorpe was also influenced by discussions already underway within Hackenthorpe Medical Centre about how to reduce smoking prevalence in the area. Alongside this, Sheffield’s Public Health Team launched the Smokefree Sheffield initiative focused on achieving the UK Government’s target of a 5% smoking rate by 2030 across the city. This presented an opportunity to use Connecting Health Communities in Sheffield to examine how local and city-level discussions and actions could be linked.

Who was involved?

Those of us leading the work in Hackenthorpe have a strong connection with the area, which helps: ‘The people here are like my grandma or my dad, so I can relate to them and understand the psychology behind their decisions’.

- Hackenthorpe Medical Centre led the work and coordinated colleagues’ involvement across the health system.

- Public health leads provided evidence on ‘what works’ in smoking and helped to link the work in Hackenthorpe to the Smokefree Sheffield work.

- Health professionals shared data about population needs and offered smoking cessation services or nicotine replacement. They included clinicians, providers and commissioners.

- Voluntary and community sector colleagues who knew the communities and understood how to build trust. They included community social prescribers who were vital in understanding needs and delivering services:

Each member viewed the world through a different lens. So, our task was to create enough alignment to move forward in a partnership way.’

‘Having everyone in the room sharing their expertise and discussing how we can join it all up – including the people who held the purse strings – was really useful.

What did we do?

We led two workshops where health and voluntary sector colleagues were brought together to identify barriers, gather learning, generate ideas, and identify and review actions.

Examples of barriers to reducing smoking

Some of the barriers included the availability of cheap, illicit tobacco; ‘smoking less’ services not always being connected to GP surgeries; the wider inequalities individuals face making lifestyle changes less of a priority; or feeling defeated by previous failed attempts to quit smoking.

Key actions that were explored and developed in between the two workshops were:

- Smokefree Sheffield linked to Hackenthorpe: Laura Davies (Hackenthorpe Surgery) and Sarah Hepworth (Public Health) worked together to look at how the Sheffield-wide initiatives being developed as part of Smokefree Sheffield could be applied within Hackenthorpe. In addition, learning from the application of tobacco control measures in Hackenthorpe is being fed back into discussions and adaptations to the Smokefree Sheffield work.

- Community Connector: Hackenthorpe Surgery and My Woodhouse District Community Forum worked together to develop a role description and approach for recruiting a Community Link Worker (with support from Woodhouse Community Centre) who would do community outreach work on reducing smoking prevalence, e.g. talking at parent and toddler groups.

- Training for social prescribers and volunteers: Developed to equip them to disseminate information to patients about reducing smoking prevalence.

- Making smoking reduction support more easily accessible: Working on a process to enable patients to move between GP surgeries to access smoking reduction support.

- Smoke-free sites: Hackenthorpe Surgery started the process of becoming a smoke-free site along with other GP surgeries in Townships1 PCN.

- Identifying opportunities for local partnerships/collaboration: For example, linking up reducing smoking work with the local walking group that runs group walks and consultations on leading a healthy life and provides diet and lifestyle advice.

It’s been brilliant to see people getting on with the project and finding new ways to create change. We’re actually making a difference for people in the Hackenthorpe area. That gives me a lot of energy.

What’s happened since?

Rather than referring someone to a 12-week ‘stop smoking’ programme, it is more about supporting people on their journey to one day being smoke-free:

At the heart of the approach is the brief intervention: a conversation to help them realise that smoking doesn’t have to define them.

Through the collaboration, the PCN gained a much deeper understanding of the reasons people struggle to stop smoking:

We learnt that conversations about smoking need to go way beyond signposting. You need to acknowledge that stopping smoking might not even be in their top 10 things to worry about. They might be thinking, “My partner’s left me, my kid’s being bullied, and I can’t pay the rent”.

At Hackenthorpe Medical Practice, patients are now referred to a charity-funded Community Connector – herself a former smoker from the local community. She works alongside the person and builds trust, finding solutions to some of their problems by referring to support with housing or finances, and helping them think through their relationship with smoking. The Community Connector role (funded by Townships1 PCN) is part of the smoke-free referral service[3], as they have the trained staff to enable a quit attempt/prescribe Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT).

This joined-up approach reflects the complex realities of people’s lives rather than treating smoking as one isolated factor.

It is also about changing social norms:

I saw a patient whose partner, parents and grandparents all smoked. She believed that all her family would always be smokers. Then I asked, “Does your little boy smoke?”, and this opened up a conversation about her dreams for his future. She did give up – and now she’s a role model within that family showing that change is possible.

Other changes included:

- Inviting patients to opt out of referral to smoking cessation rather than opting in – the former approach makes people significantly more likely to quit.

- Providing training in smoke-free services to all staff across healthcare, so that anyone, clinical or non-clinical, can confidently talk to patients about smoking.

- A new smoke-free culture being evident across the PCN, with highly visible smoking support information and even receptionists giving smoke-free advice.

- An increase in the number of referrals. It is too early to see an impact on smoking figures, but we hope this will filter through.

Even though we were talking about smoking, actually this was a way in for us all to work more closely together on health inequalities going forwards.

Tips for clinical teams

- GPs or Clinical Directors may feel they don’t have time to do this work. However, their main task is simply to bring the right people into the room and provide sponsorship. Then, others can run the project.

- Empower delivery staff at all levels to lead projects – especially those with professional expertise; but also those who come with a real understanding of and ability to speak to the local community.

- Allow failure. Give colleagues permission to try things out and see what happens.

- Think carefully about measurement. Smoking is a deeply entrenched habit, and the intervention may not reduce smoking levels in just six months. So, gather process measures and qualitative insights along the way, such as the number of people signposted, how involved people feel in decisions about smoking, or how confident staff feel.

- Recognise that every contact counts and think creatively about ways to connect with communities.

- Don’t require Community Connectors to be an expert in a particular medical area – their key strengths should be in going out and building trust and letting people know what is available.

- Be aware that external factors, such as mergers with other practices, will skew your data.

- Success in this type of work is all about the human connection – first, among stakeholders in the group and, later, between the services and the people you want to support.

- Use an intergenerational approach – engaging whole families rather than just individuals.

Sharing learning across Sheffield PCNs

Participants in this work also coordinated with other aligned groups across Sheffield that were looking at other health inequalities. The focus of the work in the other three areas that took part in Connecting Health Communities was:

- GPA1 – Increasing access to and take-up of blood pressure testing in GPA1, with a focus on individuals with severe mental illness.

- Heeley Plus – Increasing take-up of cancer screening among individuals with severe mental illness.

- SAPA5 – Developing a new approach to personalised care

The focus has been to ‘join it all up with the big city network, which is connected by a person-centred vision’.

We shared learning. Even though we were all working on different topics, many of these approaches can be used as a blueprint to take into other PCNs, or translate to other health inequality issues.

Five themes emerged from the cross-PCN discussions to take forward in the longer term:

- Making the resources available to enable long-term, cross-sector, neighbourhood work (including people and finance).

- Taking health-related actions into communities – linking health with wider lifestyle change and empowerment.

- Promoting distributed, diverse, invested-in leadership and structures and power sharing.

- Cultural shifts among health and care planning and delivery, for example, community-based nurses playing a role in strategic planning.

- Working across boundaries between organisations of all sizes spanning health, housing, employment, fundholders and frontline workers.

By: Julie Kay, Project Coordinator, Older People’s Parliament and Karen Livesey, Director, One Wirral Community Interest Company (CIC), Strategy and Transformation Lead at Healthier South Wirral PCN and Co-chair of the Wirral’s Core20plus5 Action Group

Asking older people what works for them in the Wirral

Wirral is home to an estimated 71,030 older people. While there is a good menu of support and services to address various health inequalities older people face in Wirral, they aren’t joined up. People aren’t currently accessing all the support available, with some falling through the gaps and their quality of life deteriorating, particularly those at risk due to poor mental health, isolation, low literacy and the Cost of Living crisis. However, they are currently not in contact with any services:

By falling through the net, we mean the event or events that result in the structures, systems and processes we think we have in place for people still not being enough to keep people safe, well and receiving the care and support that they need in the right place and at the right time.’

‘We can’t get to these people [ones falling through the net] but the debt collectors can.

Wirral has a mixed demographic population, including some areas with high levels of unemployment, leading to further deprivation in later life. The issue of older people falling through the net comes up time and time again. Whether you see the problem as people not accessing services, or services not accessing people – either way, this results in health inequalities for older people.

As VCSE partners, we wanted to explore ways to gather older people’s insights to inform the design of better, more relevant, local healthcare services that work for them.

Who was involved?

Wirral Older People’s Parliament agreed to join a group of core partners – Age UK Wirral, One Wirral, Healthwatch Wirral and Citizens Advice Wirral – who wanted to expand their reach to work with community groups led by older people. The group started by contacting their members and other contacts on their databases, ensuring that equal access was at the top of their mind right from the start – thinking not only who to invite but also how to invite them, and how to run events in a way that did not digitally exclude anyone.

Over the course of the programme, several other organisations became involved, including NHS Wirral Talking Therapies, NHS commissioners and local authority representatives – notably, public health experts. Older people and carers were vital to the process because the approach centred on gathering their views and understanding their lived experiences.

What we did

The first workshop explored some open questions, such as ‘What helps you to feel well and keep well?’, ‘What stops you from looking after yourself or getting help from others?’, ‘What would make the most difference to you?’ and ‘What needs to change?’ These questions helped people start to share their experiences and ideas, providing rich insights.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the partnership had some challenges recruiting those older people whose voices are seldom heard. Some heard about the first event by word of mouth, and others had been offered a lift, but most attendees were already connected with services. Nevertheless, all the participating older people experienced some health inequalities and could reflect the experiences of others they knew.

At the next workshop, people were encouraged to bring a friend or neighbour, which encouraged some new attendees who were not previously known to services. Additionally, Age UK Wirral personally approached carers they supported and encouraged them to attend. At this event, participants discussed the difficulties that carers have accessing healthcare and other services – for themselves and the people they care for. The stories shared by older people and carers clearly highlighted that many were unaware of the available support or what they were entitled to. Some felt that language used by healthcare professionals, such as GPs, further isolated them; sentiments such as ‘this is what your marriage vows are for‘ suggested that if a carer were struggling, they would have to ‘get on with it’ on their own.

Barriers to access and participation by older people

Digital barriers like feeling forced to use the internet, no digital access to online events and services, not the same level of satisfaction or connection from online services/events and a digital overload with applications and emails.

Transport challenges including senior bus passes not being valid at certain times, not feeling safe to travel (particularly alone or at night), poor accessibility for those with mobility issues and inability to access green spaces.

Discrimination in agencies and councils, being seen as ‘too old’ to contribute to the community, lack of stimulating and age-appropriate activities in residential care homes and lack of choices for their own health and wellbeing.

Lack of connections and isolation due to not knowing what is out there or how to access it, lacking confidence and not having people to go to events with, the perception of ‘I’m too old’ and ‘There’s nothing to do in the Wirral’, not knowing how to connect and talk to each other and being afraid to ask: ‘Not wanting to moan about my health’.

This workshop was also valuable as commissioners attended, meaning they heard first-hand the struggles that older people and carers face in accessing services:

One meeting was attended by strategic commissioning leads from the health authority. That was really useful, as they could hear people’s experiences first hand and people could challenge them on the spot.

Through the course of the programme, the group gathered insights about factors that make it hard for older people to access services and have their voices heard in developing services. This needed to be done in a way that created psychological safety (remembering that some insights shared would be incredibly personal, we signposted people to support, and acknowledged that not everyone would be comfortable sharing personal experiences). We used well-known community spaces where people already gather, and shared actions and next steps throughout their involvement, so that they knew that their engagement mattered.

What’s happened since our workshops?

Having gathered the insights, a key aim was to share them with decision-makers to influence future service design. This took the form of:

- A Charter for Older People, co-designed by older people and carers alongside the project steering group. This is a checklist to help commissioners ensure that any new service or existing service for older people and carers is fit for purpose.

- An equalities impact ‘How-to guide’ which covers:

- Tips for designing and delivering services to support older people and their needs.

- Assessing and taking action to address the impact of services on older people at risk of falling through the net.

What did we achieve through working in partnership?

Reporting back to older people and carers throughout the programme was not just a key aim but a vital priority too. Over the years, our members have been to many consultations and audits, and 99 out of 100 of them have gone nowhere. So – understandably – they are very cynical about participation. It was imperative that when we gathered people’s views, the impact of this process and future actions should be shared back, which also helps older people and carers hold partners to account.

Better service design: Engaging through this process, with its various strategic/problem-solving conversations, has resulted in finding solutions that ensure older people feel heard and listened to.

Information and insights shared: When different groups of people come into sessions, we start the discussion by exploring what each group knows and doesn’t know. This provides an opportunity to discover, learn and share across sectors.

Good relationships developed: A dialogue between local organisations, residents, and commissioners of council and NHS services for older people has taken place. Whilst this dialogue has always existed, the way we have brought groups together has led to more impactful engagement, in part because we met older people ‘where they are’ to develop practical support, e.g., Age UK Wirral have spoken about how their engagement with older people has shifted their strategy and that they will be focusing more directly on age discrimination. Various conversations have pointed to ‘what does it mean to engage well’, included in the ‘How-to guide’ we have created.

Expertise developed: For organisations like the Wirral Older People’s Parliament, finding new approaches to consultation with older people was essential, so they could influence future ways of working.

Improved cross-sector working: Community, Voluntary and Faith (CVF) sector participants have reported seeing more engagement from public health professionals because this work was directly informed by older people and carers’ lived experiences. It helps that some have attended a workshop and spoken to participants.

A better sense of what needs to change: Discussions during steering group meetings and events with older people and carers highlighted a range of small changes that could make older people more likely to engage – either with consultation or with services themselves:

We learned through the process that some of the answers are very simple and don’t always need to cost anything. There are some easy wins, like developing an understanding of older people among staff. Even in older people’s services, a surprising lack of awareness exists.

Next steps: We plan to have an online launch of the ‘How-to guide’ to show commissioners how to use it, and have booked conversations with service design commissioners and various strategic health leads to share the guide and ‘charter’, including the Quality Insights team, those involved in the new Health and Wellbeing strategy under the ‘Neighbourhoods’ priority, those reviewing the Community Connector role (to extend beyond working-age people) and embedding approaches in Equality Impact Assessments (so we can strive for higher quality EIAs).

There are plans for an older people’s conference in partnership with Wiral Older People’s Parliament and Public Health. Age UK plans to film older people’s individual stories to showcase their experience of age discrimination and highlight difficulties they face accessing services – these will then be shown to commissioners and other key decision-makers when designing services for older people. NHS Wirral Talking Therapies are introducing satellite hubs, so that services can move to where older people are, rather than expecting older people to ‘come to us’.

Meet the delivery team

Meet some of the people who help to connect health communities.

We are from the kinds of organisations and communities that we seek to serve. Having worked in and around the voluntary sector as volunteers, paid staff, leaders, trustees, teachers and researchers – we understand and care about the distinctiveness and independence of the sector.

Sonakshi Anand

Programme Manager, Area Lead and Co-facilitator

Keeva Rooney

Area Lead and Co-facilitator

Charlotte Pace

Facilitator

Helen Garforth

Facilitator

Katie Turner

Facilitator and Programme Supervisor

Houda Davis

Area Lead and Co-facilitator

Alexandra Parker

Area Lead and Co-facilitator

Annie Caffyn

Area Lead and Co-facilitator

(on maternity leave)

You may also be interested in

Listening to what really matters

Four stories of how communities shape health and wellbeing Connecting Health Communities, 2023-25 This…

Better health, together: Four local partnerships in action

From tackling loneliness in St Helens to building trust around TB in Crewe –…

What does it take to build effective solutions and services for our communities?

Building effective health and care solutions or services that address complex community needs and…