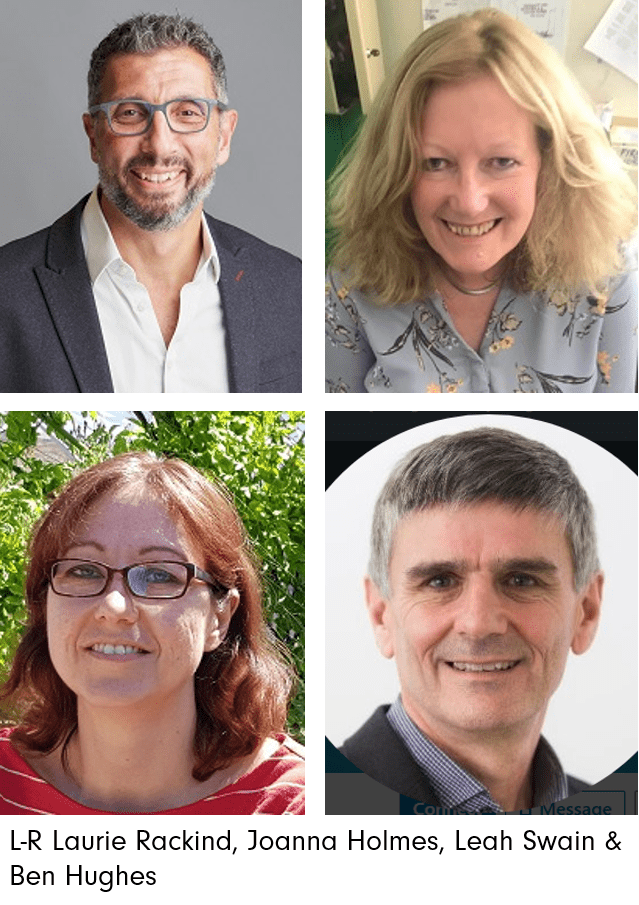

This blog is complemented by the perspectives of four practitioners who have led merger processes.

IVAR has learned much over the last two decades about what makes a merger successful. How much of this can applied in the current circumstances?

23 years ago, as chair of an alliance of regional HIV charities, I asked colleagues a simple question about our futures: “If we were to design a voluntary sector response to the challenge of HIV and AIDS from scratch, how would we organise ourselves?” The answer was a single, national organisation. A vehicle with the potential to achieve two essential public benefits: enhanced equity and quality of services; and a louder and more powerful voice with policy-makers and funders. 18 months later, four of our organisations merged into Terrence Higgins Trust, followed a year later by London Lighthouse and, over time, others.

This approach was rooted in a belief that organisations are a means to an end, and that there might be a better way of meeting charitable objects. We know that mergers entered into out of strategic choice seem most likely to yield benefits to beneficiaries (e.g. more and better services) and organisations (e.g. greater influence). However, even this ideal kind of merger requires time, money and an element of risk-taking: after all, mergers are an inexact science. For all the due diligence in the world, they always require a leap of faith.

Through the work that we have been carrying out over the course of the last few months, tracking and supporting the response of smaller VCSE organisations to the Covid-19 crisis, we have observed their extraordinary resilience, creativity and integrity. This is a precious resource and needs to be understood, valued and nurtured. At the same time, we recognise that, for a myriad of reasons, the possibility of merger is beginning to loom large for many of these organisations. Leaders are feeling frustrated, worried, and unsure about how to shift gear out of crisis and into recovery. Faced with daunting challenges – funding cliff edges and sky-high demand for services – some are beginning to look at merger as a way of continuing to deliver for their beneficiaries. The challenge is that the conditions and resources for careful, constructive mergers are less likely to be in place at the moment: organisations are feeling anxious, and the space for thinking creatively about the future is squeezed.

So, when thoughts turn to merger, how can leaders respond in ways that feel authentic and useful?

If we strip the insights and guidance of Thinking about Merger down to their bare bones, five things stand out:

- After the 2008 financial crisis, we found that organisations were more likely to survive and, over time, thrive if they were open to asking themselves fundamental questions such as: Who are we? What are we trying to achieve? What is the best vehicle to make that happen? At a moment of crisis, there may also be an opportunity to focus minds and bring the possibility of merger into discussions about the future.

- For organisations with their backs against the wall, the proposition may be: the preservation of something versus the gradual disappearance of everything. But even if you enter merger explorations on the back foot – preoccupied, say, by survival rather than growth – it’s still important to identify and then pursue a positive agenda about change. Keeping a service going might not feel like the most compelling vision, but that may be the vision that is possible right now.

- However bleak your prospects, merger may not be the answer. In addition to a shared vision, you need a feel for the fit with your potential partner(s). Do you have enough in common, enough shared values, to trust in the potential of a merger to work? There is no shame in concluding not. We have written before about the importance of having an ‘awareness of mortality’. For organisations whose aims are no longer appropriate, or for whom sources of public funding on which they were overwhelmingly dependent no longer exist, or who have not been able to make a transition to a new environment or find a sustainable alternative business model, it may be more responsible to close down rather than compete with others or struggle on, hand to mouth. Or there may be steps short of merger that can at least preserve some of what has been achieved – such as hiving off a non-loss-making service, or simply much closer collaboration.

- Under normal circumstances, we would encourage possible merger partners to think about possible deal breakers upstream. These might include questions of identity (including name and brand), location, service model, and staffing. Without the luxury of time, or resources to support a staged process, it will still be important to articulate and be mindful of what each partner is not prepared to give up or take on. Without, at best, addressing these ‘red lines’ or, at worst, putting in place plans to do so, the risk of failure will increase.

- Finally, there is one key deal breaker which will need to be resolved as early as possible in the process: leadership. Here, as with all design considerations in a merger, form needs to follow function. In other words, what kind of leadership will the new, merged entity require to give it the best chance of succeeding?

IVAR and Bates Wells are working on a new edition of Thinking about Merger to support charities navigating the particular challenges presented by Covid-19. Sign up to our newsletter and be the first to know when this is released.

The key features and stages of merger are outlined in Thinking about Merger, and described in more detail in the Locality and TACT case studies.